|

Pelican

This champion "little ship"

is easy to

build, sail, handle, own and love.

by William H. Short

Reprinted from "Build 20 Small Boats" - 1966

The Annual San Francisco Trans-Bay Pelican Race

has already become a popular classic. On June 11, 1966, the big

event attracted Pelicans from. all over California and Washington,

and forty-two Pelicans participated. The race to San Francisco

from Sausalito and return now includes a windward leg to test

the Pelican's tacking ability. She is smart to windward, too.

Not a single Pelican capsized or met any trouble this year, although

the afternoon breezes were fresh as ever.

Throughout the planning research for the Pelican,

the designer kept firmly in mind the challenge of San Francisco

Bay's strong winds and rough water. At the same time he was aiming

at a design simple to handle—and fast. The Pelican is a

little craft capable of safely crossing San

Francisco Bay's main ship channel west of Alcatraz (the weather

side) from Marin to San Francisco in the strong afternoon winds.

On the face of it, none of this seems impressive, until the size

and type of boat is known—a stalwart 12-foot centerboarder.

Chloe, the original

Pelican, passed all her heavy-weather channel tests with flying

colors. An article appearing in Rudder, May 1963, thoroughly describes

her sailing characteristics. Briefly, her great stability and

buoyancy are created by combining the lines of the famous Banks

fishing dory with the Oriental sampan. Foredecks, side decks and

ample stern deck, make her exceptionally dry. Real coamings around

the entire cockpit complete her corkiness. The combination of

resilient lug rig and the great flare and freeboard of her beamy

topsides make her outstandingly safe.

The Pelican can be sailed either

as a lug cat or lug stoop rig. The regular cat lug is not changed

in any way, nor is the mast shifted. Big and long, the plywood

centerhoard can he swung forward enough to balance the helm nicely,

when sailing with the jib. In brisk winds the mainsail is certainly

all that is needed. (72 sq. ft. main, not counting

large roach, and 33 sq. ft. in the jib.) She will plane and surf

serenely, often when larger boats are starting to seek shelter.

CONSTRUCTION

(click to enlarge) |

Basically, the hull is formed of

three sheets of plywood; only one piece for the bottom and one

panel for each side. These three sheets are joined together by

a transom bow and a transom, stern, and two longitudinals or "chine

logs" (running fore and aft inside—to connect the dory

bottom to the flaring sides). An interesting fringe benefit in

the joinery work lies in these chine logs;

their bevel angle or flare angle is CONSTANT clear fore and aft,

from stem to stern. So the chines can be ordered pre-bevelled

from the mill, and this eliminates a lot of hand faring or bevel

adjusting labor.

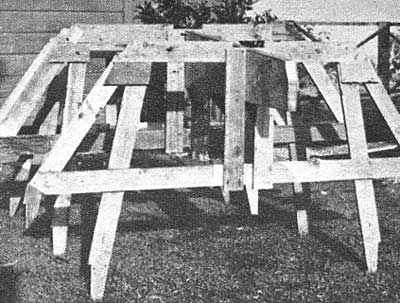

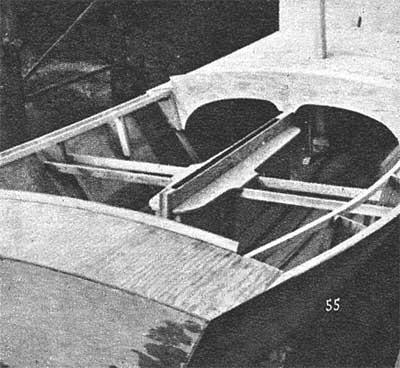

Pelicans

are built upside down. upon their simple (five-part) jig. Her

bow and stern transoms do double duty as hull end forms while

she is building on her jig. There are four mold forms (made of

2 x 4's and 2 x 6's, these stay with the jig). The four mold forms

and the big 2 x 12 strongback complete the building jig. No lofting

is necessary. Pelican lofts herself. The bevel angles given in

the blueprints for her chines and transom frames render it unnecessary

to loft any part of her. All bevels and dimensions have been thoroughly

proven.

Pelicans are built upside down on simple

jig.

Transom bow and stern are end forms.

After the

6" wide laminated plywood keelson is pulled down on the strongback

with wires and turnbuckles, or ''Spanish. windlasses" (from

underneath. the jig) and transoms attached via their knees to

keelson; the prebevelled chines are bent into place over the jig

and attached to transoms. Wire and turnbuckles are used here,

too, to hold chines down while work is completed.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge) |

Limber, straight grain air-dried

spruce is recommended for these husky

chine logs. Her chine logs are quite large in cross-section for

a 12' boat, but it's mighty nice to have a positively Weldwood-glued

and bronze-fastened bottom that will last a lifetime. Douglas

fir chines have been used, but because of its stiffness, this

material had to be laminated on 'the jig to facilitate the bending

operation. Note the unorthodox but very strong and simple method

of securing the chine ends to transoms with chine stopper blocks

of plywood, rather than notching out transom frames. This new

method eliminates a lot of awkward bevel notching, joinery work

and also guarantees a wider faying surface of transom frame near

edge of chine to prevent chances of leaking.

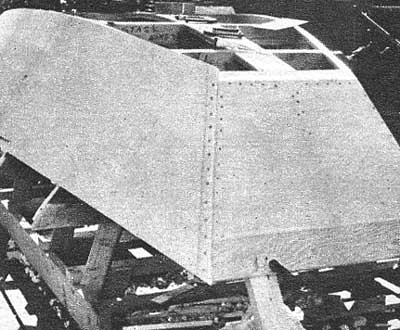

Next, the 2-foot wide 3/8"

thick plywood side panels are attached to the chines and the transoms.

Then the single, 3/8" -thick 4-foot wide bottom panel is

fastened in place on keelson and chines; it overlaps the side

panel. This ''planking job'' is glued and bronze boat-nailed to

keelson, to chines and transoms. Bronze "Everhold" or

"Anchorfast" serrated boat nails are faster and much

easier to use than screws and better holding in most areas. Large

screws, however, are used in very "springy" places,

like fastening the forward ends of panels to the transom frames

where one cannot easily hold down work while nailing.

Sides are 2ft wide 3/8" plywood panels

which are glued and bronze-nailed in place.

The 6-inch wide plywood keelson,

composed of two layers of half-inch plywood, laminated down one

layer at a time, is broad enough to allow very wide trunk bedlogs

to secure to it. And the laminated down, trunk bedlogs, provide

2-inch wide surface-to-surface contact with keelson, guaranteeing

watertight integrity and tremendous laminated strength. These

bedlogs are laminated down to keelson with bronze screws. C-clamps

are placed through centerboard slot to create thorough pressure

while gluing and screwing down.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge) |

Trunk headledges are not thrust

down clear through bottom of boat as in orthodox practice, but

are buried and thoroughly glued 2 inches deep between the husky

bedlogs and stand on keelson. Thus there is no end grain of headledges

exposed through bottom. Centerboard trunk panel sides are glued

and screwed to bedlogs and headledges and they, too, have a 2-inch

bury and surface to surface contact to their bedlogs. Forward

headledge is secured to main deck beam. After headledge is secured

with wide knee to keelson and to floor timber.

After the waterproof glue dries,

she is taken off the jig, turned right side up, precut sheer clamp

and the four laminated deck beams installed. These parts and the

centerboard bedlogs and trunk are all installed after the boat

is upright and off the jig.

After single-sheet 4ft. wide bottom is

fastened, turn hull upright for top work.

Footlings are glued fore and aft

to the inside of the bottom of the boat to further stiffen and

provide good footing.

The deck beams are butted into

sheer clamp and attached with plywood knees to vertical frame

batten beneath sheer clamp. The only purpose of the side frame

battens is to support and secure deck beams, their knees, and

the side deck knees, and the thwart riser and

its knees.

The external stempost is not only

a strengthening member, but is used as a gammon head to snap the

plank type (plywood) bowsprit down over. Also the forestay tang

secures to it. And this stempost makes trailering easier for it

nestles into the standard trailer's winch-post bowsaddle.

The mast is 2" x 3'' spruce.

Boom and gaff are from 2'' x 2'' spruce. Approximately 12-inch

wide plywood coamings reach deep into the cockpit and provide

great box beam and cantilever strength to the entire hull, for

they combine with the side deck knees, completing triangular box

beam rigidity.

The shrouds are 3/8-inch nonstretch

dacron rope, or nonstretch Samson Yacht Braid. The upped end of

the shroud is hung over the mast and onto the hound. The lower

end has an eye splice around a thimble so that it can be secured

by the old lanyard method to the chain plates' eye shackle. (Both

ends of the shroud are eye-spliced.) There are no gadgets or tricky

hardware in her rigging. Her chain plates are secured to the outside

of the hull, bolted with three bolts through large half-inch plywood

plate with washers and nuts on the inside. The entire boat, with

passengers, could be picked up with a crane, hooked on to a single

shroud.

The main halyard is nonstretch

3/8-inch dacron rope. The main halyard block is a 5-inch shell

and 2-3/4-inch diameter sheave, a big enough sheave so as not

to chafe the halyard through, as little sheaves will do. This

important block is hung by a 3/8-inch diameter dacron strap, choked

on to the mast over the shrouds hounds with a lark'shead bend.

The bowsprit is very quickly rigged.

When sailing the jib does not have to be rigged or set to keep

the bowsprit from sagging, for the bowsprit is thrust into place

under a hold down block on the forward edge of the mast. The regular

forestay stays with the boat whether sailing cat rigged or sloop

rigged. (This forestay is attached to the stempost tang.) The

double jib sheets lead outside and around this forestay and the

shrouds. The bowsprit bobstay is permanently spliced to the outer

end of the bowsprit but has a quick release Pelican hook that

can be secured into the towing ring eye at the bottom of the bow

transom.

|