|

The Stasha,

the world’s lightest nesting dinghy weighs as much as

a baby bird (wandering albatross chick). |

There’s a saying that I like. ‘If you get in a car

and don’t know where you’re going, you’ll never

get there’. Designing a boat is a bit like this as you need

to know a few things before you can begin. Knowing where to start

is easier said than done. So many things can influence the design.

I have found that a good place to start is to first think about

what you don’t want. For example, I didn’t want a

heavy dinghy. Nothing spoils the dinghy experience more than a

weighty tender that is hard to move about and stow. This was my

starting point. No matter what shape or size of dinghy I came

up with it wouldn’t be a heavy one!

For years, I’d been intrigued by boats I’d seen

in America that were made using materials from light aircraft.

Constructed from a framework of wood and covered in cloth, they

looked fragile but were obviously quite tough and since I was

determined to keep the weight down I would also have to employ

a similar system. So deciding what I didn’t want from my

dinghy led me to the construction technique I was going to use.

However, there’s no point having a light dinghy if you

have no where to put it. My yacht is just 24 feet long and the

only place I could think of to stow a dinghy where it wouldn’t

be in the way, look ugly or be unseaworthy was on the tiny foredeck.

I got my tape measure out and discovered that it was about 4 feet

wide at the aft end where the cabin begins and was a bit more

than 4 feet from there to the bows. So it would have to be a nesting

dinghy. In theory it could be about 7 feet long when assembled

and that was a good size for a small yacht. And so was born the

idea of making a super lightweight nesting dinghy.

|

Stasha dinghy, nested and stowed on the deck

of a Pacific Seacraft Dana 24. |

There’s not much point worrying about aesthetics when

you are designing a dinghy, the most important thing in my opinion

is stability. There is nothing worse than a tippy dinghy, except

perhaps a heavy tippy dinghy. Light boats are less stable than

heavy boats so I would be relying mainly on the shape of the boat

to provide stability. This meant that it had to be as square as

possible. I now had enough information to design the boat’s

shape.

The rest of it would be guesswork based on experience. What would

happen if I cut a boat in half to make it nest? Would it be strong

enough? What kind of forces would the join be under? How would

the stringers attach to the end panels? These and many more questions

filled my brain. As far as I could tell, no one had ever built

a dinghy like this and I wondered why. Have people tried it but

drowned during testing or has no one ever tried? Maybe it was

a stupid idea that would never work but one of the great beauties

of a lightweight boat is that they are cheap to build. Less materials

means less cost. I could afford to simply make a boat and see

if it worked.

Normally nesting dinghies are made so that the front section

comes off and fits inside the rear section but this does not seem

logical to me for many reasons. The shape of the front section

always needs to be quite pointed but this reduces stability too

much. It also means that the interior volume of the dinghy is

much reduced so you might have an eight foot nesting dinghy but

it will feel much smaller. Then there’s the rowing position.

It’s perfectly logical to put a thwart on or above the join

but it leads to a bows down attitude when rowing which makes the

dinghy hard to row and just looks wrong. Rowing is easier when

the bows are slightly up.

The whole concept seemed flawed to me so I tried a bit of lateral

thinking and did some sketches with the rear section fitting into

the front section and suddenly everything started to make more

sense. The most obvious problem with doing it this way around

was that the rear section would be slightly narrower than the

front which would mean a step where they join. In fact this is

not a problem as the bottom of the dinghy remains flush, it’s

just the sides that have a small step. I doubted if it would make

an appreciable difference to the finished boat’s performance.

|

Sunlight glows through the translucent skin

of the Stasha. Note the small step at the join. |

This one compromise seemed a small price to pay for the host

of advantages that it brought the design. I could have a fairly

fine bow, a good interior volume, great stability and a perfect

rowing position. Another bonus with this set up is that the rowing

position doesn’t have to change when you take a passenger.

Not only this but if the passenger sits in the front section back

to back with the rower, the combined weight is centred in the

boat increasing stability still further and each occupant has

a clear, unobstructed view of their surroundings. This is much

more pleasant for everyone. Yet another advantage was the fact

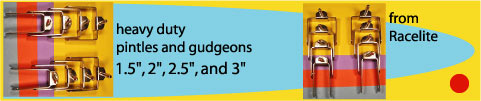

that the pintles for the rudder are stowed inside the nested boat

so ropes can’t get caught on them.

To simplify the building process, I decided to do away with any

hint of sheer and make the top of the boat completely straight.

Simplifying the wood requirements would also make the boat easier

and cheaper to build. Now I had all the information I needed to

start to design the boat. I made a few sketches just to see how

it would look. Although it was boxy it still had a nice boat like

shape which was pleasing.

Next I made a 1 -10 scale cardboard model 220mm long. I wanted

a near flat bottom for maximum stability and ease of build but

I suspected that the fine framework allied with the pressure of

the water on the hull would flex inwards so I incorporated a slight

V into the bottom. This would also add more strength to the structure.

The sides are almost upright, with only a slight angle outwards.

Again, this increases interior volume and stability.

The simplest way to build a boat like this is to make a jig.

Panels are cut out and screwed to the jig and then the stringers

and ribs are attached to it to create the framework. Happy with

my cardboard model I divided it up into 5 sections and used these

measurements to make the stations that would dictate it’s

shape. I scaled up the measurements by simply adding a zero. Then

these measurements were converted into instructions using the

simple ‘join the dots’ principal that all Woodenwidget

dinghies are built with.

|

This photo shows the jig for the front section

with all panels, stringers and ribs in place. |

Deciding how many stringers and ribs to use was decided by guesswork

based on experience and finally what ‘looks right’

while trying to minimise weight and keep the build simple. Obviously

the more ribs you have the more work there is to make and fit

them. Since lack of weight was everything I did err on the light

side.

The end panels on the jig stay as part of the boat while the

inner stations are only temporary. The end panels have slots cut

in them to accommodate the stringers which are then glued in with

epoxy resin. The stringers are held in place on the inner stations

with cable ties. The following day the ribs are made and glued

in place. The ribs are glued everywhere they touch a stringer.

This gives over 60 glue joins which makes for a surprisingly strong

structure.

The making of the ribs caused me some concern. On the one hand

I wanted the dinghy to be easy to build but it had to be light

too. I considered a system that had no bent ribs but it meant

making nearly 40 mortises which would take a long time and require

a certain skill. It would also add weight and complication. So

I decided to take a fresh look at bending ribs with heat.

At some point most boat builders will have a go at steaming

wood. It’s a lot of fun and it’s amazing what you

can put a piece of wood through before it breaks. If you want

to really understand wood this is a great way to do it. You will

walk away with a new respect for it as a material.

Some woods bend easier than others so I chose ash because it

is strong and light as well as easy to bend. The straightness

and orientation of the grain plays a big part in how far you can

bend wood as does the amount of moisture content. Thin wood bends

easier than thick wood but in any case you’ll need heat.

Most boat builders will construct a steam box to do this but since

there are only 9 ribs to be bent in the Stasha I needed to find

a simpler way.

Pre soaking the wood for a couple of days is essential. Once

the wood is completely saturated, they are fitted to the jig.

The centre is clamped to the keel and each side of the rib is

pushed down while applying heat from a hot air gun. The ribs are

pushed down in gradual stages until they touch at all the stringers.

This is a little time consuming and it helps to have patience

but still easier than any other system I could devise. It’s

also the lightest way and gives the dinghy a nice rounded boat

shape. This also makes it easier to fit the cloth later.

|

This shot shows one of the ribs being gradually

persuaded into place with heat from a hot air gun. |

The ribs are then glued where they touch at all the stringers.

A day later the structure can be removed from the jig. It’s

still quite floppy but gets much stronger at every stage. (To

save wood, the stations are cut down to make the jig for the rear

section of the dinghy). Inner gunwales and reinforcing knees are

added for strength and that’s basically all there is to

the wooden structure. Not one screw in it. It’s thanks to

the amazing bonding strength of epoxy that a construction so light

is even possible.

|

Here’s the framework for the front section

complete, just awaiting the kevlar twine and the cloth. |

Now all the hard and messy work is done. All that remains is

to cover the framework with a special heat shrink Dacron cloth.

It’s attached with a product called Heat’n'Bond which

is glue on a roll. It is melted with a humble domestic iron. This

is cheap, light and very easy to use. It also sticks very well

to the cloth and has excellent sheer force qualities. This Heat’n'Bond

tape is applied to the keel, gunwales and end panels.

Now Kevlar twine is laid diagonally across the boat and glued

to the gunwales. This helps to reduce twist in the structure and

also to give more for the cloth to lay against than just the stringers.

The cloth is laid on the structure and glued to the gunwales and

end panels, then the iron is run over the cloth and all the wrinkles

and baggy bits simply disappear leaving a drum tight smooth finish.

This is very satisfying to do. The edges of the cloth are protected

by small battens of wood and finally coated with a water based

varnish but this is just one way to waterproof the fabric.

|

Here the Dacron cloth has been glued in place.

The remaining creases magically disappear when the iron is

run over it. |

Having made the two halves it was time to work out a way to join

them. There’s no point having a nesting dinghy if it can’t

be easily assembled either on land or on the water. Initially

I thought about a very minimal bulkhead for the join along with

some kind of waterproofing but that hardly seemed easy. Far better

to sacrifice a little weight and have fuller, higher bulkheads.

This means that each section is a boat in it’s own right

so there is no need to waterproof the join at all. Two simple

keyhole slots are all that is needed at the bottom of the join

and two bolts at the top. Assembly takes less than a minute.

|

Here the keyhole slot for joining the two sections

can be seen. |

What we have here is a basic 7 foot nesting rowing boat which

is probably fine for most people especially as it rows so well

but I also wanted it to sail. Because the rear section nests in

the front section, centreboards and the like are out of the question

and in any case fitting something like that would add weight and

the potential for leaks. It would also be demanding to do and

this doesn’t fit in with the easy build ethos.

Rowing Stasha |

|

The keel is bolted to the side of the boat and can swing up if

you run aground. Here the slab sides are a bonus as it gives somewhere

to attach the keel lower down. The mast support is made from two

thwarts, the upper one bolts to the top of the gunwales and the

lower one rests between the ribs below it. Diagonals of string

must be added to help spread the load from the mast. Simple, effective

and light. The mast and rudder from an Optimist is used with a

slightly cut down sail.

If you want an outboard then you’ll have to reinforce and

thicken the transom. This adds about half a kilo to the weight

of the boat. This option has also been designed to be retro fitted

at any time.

I am delighted with how well the boat has turned out. It is pretty,

very light, easy to assemble, stows beautifully and fairly unobtrusively

on the foredeck. The rowing position is excellent and very comfy.

It goes fine with up to a 3.3hp outboard and sails surprisingly

well with it’s modified Optimist rig.

|

The Stasha under sail using it’s cut down

Optimist rig. |

To be honest, I have been surprised at how well this boat works.

I had no idea if it could take the stresses from a mast and keel

or an engine but it has passed all these tests with flying colours

and I’m still here to talk about it. Someone said it seems

to ‘Dance on the water’ and it really does. It also

slips along and carries it’s way amazingly well for such

a light dinghy. Any doubts I might have had about the step in

the hull are long forgotten, it seems to make no difference whatsoever.

This can be confirmed by watching the water through the translucent

hull as it passes the step. The boat hardly leaves a mark of it’s

passing as it cuts through the water.

So this proves that if you follow sound basic small boat principals

and keep faith with your original wants and don’t wants,

you end up with a splendid little boat that is easy and fun to

build in the smallest of places. It’s cheap to make and

surprisingly tough. It stows away in a minute almost anywhere,

including the back of an estate car. It rows well, sails well,

takes and engine, two people with shopping and it does all this

while weighing the same as a Wandering Albatross chick! (about

10 kilos! Very heavy for a baby bird perhaps but extremely light

for a 7 foot dinghy).

|

The Stasha nested. It can be stowed upright

if needed. Note the kevlar twine reinforcements. |

To learn more and see some videos of the Stasha in action, please

visit https://woodenwidget.com/

Plans for Stasha are available now through Duckworks.

*****

|