Custom Search

|

| boat plans |

| canoe/kayak |

| electrical |

| epoxy/supplies |

| fasteners |

| gear |

| gift certificates |

| hardware |

| hatches/deckplates |

| media |

| paint/varnish |

| rope/line |

| rowing/sculling |

| sailmaking |

| sails |

| tools |

| join |

| home |

| indexes |

| classifieds |

| calendar |

| archives |

| about |

| links |

| Join Duckworks Get free newsletter CLICK HERE |

|

|

| Enlarged Life - Part Two |

by Wade Tarzia

- Connecticut - USA |

The 2014 Texas 200 in a Tiny BoatPart One - Part Two - Part Three - Part Four - Part Five - Part SixFirst Light-ish

The last night on land, again no sleep, and soon 5 AM arrives with a morning spiced with Andy's colorful attempts to make us shove off by 6 AM. I shovel down my boiling hot oatmeal to comply and suffer the first wounds of the voyage. Sleep deprivation became the week's theme, and if my comrades are reading this, now they know why I declined the dangerous temptation of sprawling in the cockpit to sail as they often did. I admire Andy's true grit on this matter but it goes against everything I have learned about Nomad culture. One thing I learned about the Iranian nomads (from the book, Borzu) is that the first move of the season is just for practice. The nomad chief gets everybody up, gives paternal advice about tightening straps, looking for things left behind, and going pee before mounting up. And then they travel for just an hour, an excellent way to work out the kinks after the lazy season. So in this case, we can apply a solid ethnographic analogy (though I understand this is now in disfavor among anthropologists) behind a slow morning ritual. In fact, in their wisdom the event planners made this day our shortest run (25 miles), which turned out to be a great idea. I learned how not to reef my sail (to the foot, not the boom), and several others learned how to attach their rudders properly. Nomad tradition was satisfied. The first day deserves a poem in response to Tennyson's Ulysses:

The Joy in Terror

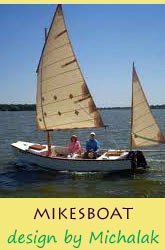

Of course terror has an important function in our weekend warrior sea-tales. It must, however, have a certain ratio with the other feelings: boredom, beauty, and wonder. The equation of operational boating experience - indeed, all human experience - can be formulated through information theory, which was first developed by communications engineers as they sought a way to describe the effects of noise vs. information. In everyday terms, the theory shows how we recognize what is important amidst all the chaos in life. (Information theory has since been used in many fields; in fact, you have just passed the first test, since you have gotten through this preamble, proving that you are the kind of person I want reading my essays; if you also sail a boat, you are as good as carrot cake, one of my favorite things.) But let me complete the explication of the important ratios introduced above. Routine eats away at perception (i.e., highway hypnosis). In contrast, a superfluity of Terror squeezes much perception into little spaces, but in such times we often die, which reduces perception. Beauty is OK, but too much of it redefines what beauty, then, back to Routine. A bucket load of Wonder makes us wander, because in the end, wonder doesn't go anywhere, and we humans want at least a few answers. In short, if the balance of terror, boredom, wonder, and beauty are just so, that's as good as an experience can get. Now we can finally start the first day with a functional theory. The first day of anything is the most exciting if only because Terror has not yet had time to set up any routines (which creates boring Confidence). For me this was the best first day of all because I was setting off in a boat I had never sailed, exactly the opposite of all advice given for expedition sailing. Now I am a student again, sitting on my teacher's stern side-deck. Indeed, boats teach us fundamental lessons, doing so like a teacher who saves the most life-changing question for the student whose gaze has been studying the ecology outside the window. So what contradictions will the new boat teach me? How will it weather a breeze? What aspects of its own personality will delight, which will bite? My own boat is a 16 foot outrigger canoe, a rigorously instructive craft if it thinks I'm slacking off, but usually stable with comfortably deep cockpit. I kept reminding myself this new boat is four feet wide, and its stability could be imaginary. But so far, so good. As I set out at the tail end of the Duck fleet, the wind takes over out in the lagoon. She heads downwind, answering the helm as boats often do. I had set out with a reef in my lug but now see a crease appearing in the strong wind - which reveals all lies and errors - I tied the reef improperly for a loose-footed sail, to the boom rather than around the bundled foot. No real matter, it's a broad reach, will be all day, and I can fix it later. Suddenly encompassed by the comparatively wide water outside Port Mansfield, and the evidently strong wind, which had something to do with all the whitecaps, the launching was like a 18th birthday party after which a rigorous set of parents kicked me out of the house. The fleet was now far ahead; one fellow straggler drifts away too but not before I catch him in one glorious photo that captures the words "beauty" and "adventure." The sun seemed to ionize the clouds, and the sky was the glory of stellar nurseries light-years away. For some number of moments I was the luckiest person on earth. After an hour in the Duck, I prophesied crushed-butt syndrome as the 3/4 inch piece of foam pad began the rapid process of thinning out (the next day I would shift to an inflatable seat, comfy, but like sitting on ball-bearings trying to roll me overboard). But the glorious morning was a fine medicine. The wind remained strong but trusty-like that powerful friend who has not yet hurt you with his over-abundance of good will in a hearty shoulder punch. I hold out hope that the boat will not take on unasked duties of instruction. Look at its harmless name - Puddle Duck! I'm under-canvassed, reefed, and more important: humble. I profess little in front of my superiors (pretty much every sailor I've met). I have not bragged or spoken any oaths that some god with time on its hands might hear and act upon. And despite all this, when I wasn't looking, the bow slowly nosed into the foaming water, the boat tipping forward like a playground machine, the Laguna Madre hissing up the foredeck. The boat was simply saying, "I am your substitute teacher and you were enjoying yourself.'' I scooted to the very corner of the transom and brought the bow up again (better a dragging transom than a pitch-pole - isn't there some proverb about that?). Then a wave broke on the quarter, providing the morning wash-up I'd missed. I made the mistake of looking behind - row upon row of 3 and 4 foot waves, white-capping, each one capable of swamping the boat (have a look, though a wide-angle camera flattens everything down: Now I felt better, because here was a little terror, a dose of mediocre luck to bleed off the really bad luck (statistical studies surely would bear this out). The other problem of stiff weather-helm began to reveal itself. This was a problem that was not a problem as measured in increments of minutes, but over an hour the many momentary lapses of pulling that tiller into my belly meant we were drifting slowly to starboard, which I did not notice much until I saw a channel marker to port. One way to get back there was to gybe the sail in this 20 knot wind and Duck-swallowing waves - occasionally a dangerous procedure risking bodily harm and boat damage. Earlier the wind had suddenly shifted and the sail had done that fearsome thing it can do - without warning slam from one side to the other. This is a headsman's stroke on a small boat, avoided by scarcely a quarter-inch, more than adequately summarizing a samurai duel. I was reminded of a veteran sailor's comment: whenever he hears a strange sound he ducks, which once saved him from a broken sheet that unleashed a boom. This may well be excellent universal advice; duck several times a day no matter what people think. But I am delaying the story of weather-helm, just as I delayed the decision to gybe. Now, the decision is forced as we come to the place where seabirds can walk. However, my nerve failed and I decided to wear-around. This is salty talk that means turning your boat in a circle so the sail is never caught from behind and slammed over. So I turned even further to the edge of the bay, somehow got through irons and now took the full wind in the face as we tacked against it. We edged more to the west, back to the channel, though now sailing by the lee; must get the sail to the other side again. Frazzled nerves put me in an, "Oh, whatever," mood, and I gybed in a slight lull, hand carefully on the sheet, and live to write about it. People who turn their vehicles with steering wheels on the road live in a different world of changing directions, but we sailors try to learn your strange language and customs in a spirit of good will. The first day used up all its little vial of terror for me - remaining days were easy sailing, the last day being a thing in its own category. As I got into the land-cut at the end of the bay with its flat water and speedy magical sailing, the last nervous breath exited; the baptism in an unfamiliar boat was over, and we could start becoming friends. Little did I know that beyond sight my comrades were enduring real dramas. The first-day-excitement encapsulates the essence of our ordinary-folk adventures; they may seem small but nevertheless, we have rope-burns to compare, and bruises, which when they fester, make better stories, all of which evolves our personhood. We solve our problems in foundational ways, replacing torn-out hardware with a length of line we kept around anticipating such a need, pat ourselves on the back when we carried just the right kind of spare nuts and bolts, alter rigging at camp to improve the set of sail, hack down the base of a broken mast to make-do, keep alert with little games, mumbled songs, or sheer-will-focus when we dearly want to collapse. We are always solving problems, but Texas 200 - like events concentrate this utterly human activity, and so information theory (had it a voice) says, "Rejoice! You will best remember this concentrated stuff, and with that potency construct your personhoods with fast-setting adhesives, and your sparkling stories will be the fine-grit sandpaper and paint to make shine any rough remaining doubt." |

To comment on Duckworks articles, please visit one of the following:

|

|